State Data

Confidence in data for this state:

MODERATE

2018 data unless noted.

Definitions

Terms used on this website and in data sets are defined & discussed here.

Asplund Wastewater Treatment Facility in Anchorage. Photo courtesy of AWWU.

Fairbanks Wastewater Treatment Facility. Photo courtesy of GHU.

Naknek Lagoons. Photo courtesy of AK DEC.

Soldotna WRRF. Photo courtesy of City of Soldotna.

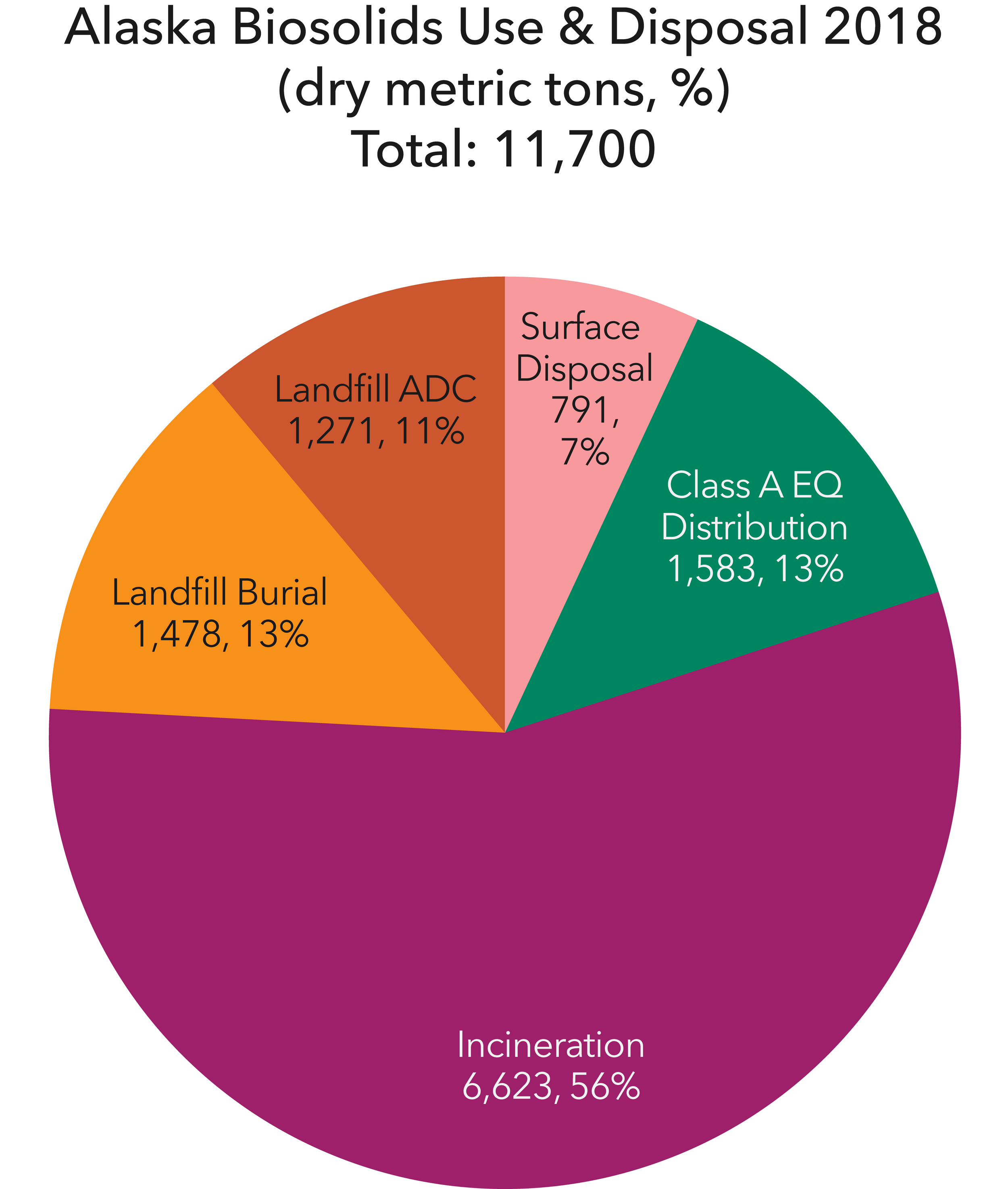

State Summary

● In Alaska, the management of wastewater solids (sludge) is handled at a very local level, given the state’s enormous rural areas and the distances between cities and towns. The vast majority of Alaska wastewater solids is disposed of in local municipal landfills or designated monofills – the cheapest options for solids management in the state.

● A few cities and large towns generate the bulk of Alaska’s wastewater solids – Anchorage, Juneau, Fairbanks, Kodiak, Ketchikan. In remote regions, residents rely on septic tanks that should have septage removed every 3 - 5 years or small facilities with sludge lagoons that are only cleaned out every 20-30 years.

● The pressures on biosolids recycling selected in the state survey response were:

COST – disposal options are least expensive

PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT – concerns of neighbors, environmental groups, and others

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

AGRICULTURAL ISSUES – limited farmland, seasonal restrictions, competition with manures, etc.

TRADITION – WWTP management doesn't care where it goes, just contracts to make it go away.

● Wastewater solids are regulated by the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), solid waste division, under 18 AAC 60, which largely mirrors the federal biosolids rule, 40 CFR Part 503. Under this code, DEC permits water resource recovery facilities (WRRFs) and other facilities that treat, dispose of, land apply, or otherwise manage wastewater solids. DEC also issues permits for biosolids and septage land application, which is not common.

● Anchorage operates the state’s only sewage sludge incinerator (SSI), a Zimpro multiple-hearth incinerator that came online in 1986, replacing an older SSI. The SSI burns solids trucked in from the Eagle River WWTP and Girdwood WWTF, as well as from Anchorage’s large WRRF (John M. Asplund Wastewater Treatment Facility, 58 MGD design capacity), which also treated about 18 million gallons of Mat-Su Borough septage in 2018, trucked in from communities as far away as Palmer. Occasionally, the SSI also receives solids from other treatment plants (Palmer, Wasilla, Talkeetna, Whittier). The SSI is old and failing; replacement would cost more than $100 million. Due to landfill space limitations, Anchorage is considering building a waste-to-energy facility, which might also burn solids that currently go to the SSI. Alternative biosolids management practices, including composting, are also being considered (as of early 2022).

● As of 2018, Fairbanks (which takes in all septage and wastewater within a radius of 150 miles),Kodiak, and likely Ketchikan composted biosolids, but only Fairbanks made the final EQ product available to the public for use as a soil amendment. Fairbanks compost has received national attention for many years because of its composting success in the cold far north. However, in June 2019, Golden Heart Utilities, the company that has long operated the Fairbanks biosolids composting system, suspended distribution of compost. “Given the uncertainty and general concerns regarding PFAS, GHU is erring on the side of caution,” notes the company’s website (http://www.akwater.com/compost.shtml). Fairbanks’ landfill will no longer accept wastewater solids or compost because of PFAS concerns. This may be the case with other landfills in AK, all of which are owned by municipalities.

● The City and Borough of Juneau (CBJ) is in the process of installing a biosolids dryer (as of 2022, https://juneau.org/engineering-public-works/utilities-division/wastewater-utility-division/biosolids ). But in 2018, some solids from CBJ’s largest WRRFs were shipped via barge to Seattle, WA, then via train to Oregon, where they were landfilled. The rest of CBJ’s wastewater solids went to an onsite sludge monofill.

● Petersburg has a 2.1 MGD WRRF that produces about 40 metric tons of solids that, since 2015 have been composted and are likely being stored. The composting program is still developing as of 2020.

● Homer has a unique wastewater treatment process that is conducted in a vertical, in-ground, 500-foot loop in which the wastewater is treated during a two-day retention time. Treatment in the ground takes advantage of moderate ground temperatures and creates a smaller facility footprint at the surface. Solids are aerobically digested, thickened in old lagoons, and dewatered in drying beds. https://www.tpomag.com/editorial/2013/09/treatment_in_depth

● Palmer, AK, has been at the center of several wastewater and biosolids management debates in recent years – debates that highlight challenges unique to Alaska: cold temperatures, high cost of hauling and disposal of waste, and active stewardship of ecosystems. Palmer sits within the Matanuska-Susitna Borough, the most agricultural area in Alaska, water from which flows into rivers full of salmon. In 2017, the borough considered a ban on land application of biosolids, with some farmers and concerned citizens citing a lack of research on biosolids land application and microbial activity in amended soils in climates as cold as Alaska’s. Those opposed to the ban cited increased costs of solids management and truck traffic on already-busy roads if solids had to be hauled to Anchorage. Both sides acknowledged the popularity and safety of biosolids land application in the Lower 48. In the end, the Borough carved out an exception to the land application ban within the incorporated city limits of Palmer, Wasilla, and Houston. Lime stabilization and application on municipal land is one biosolids and septage management practice regularly employed by Palmer, and finding an alternative solution would be expensive. In 2018, the city upgraded its wastewater treatment operations, installing a Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor (MBBR) to reduce ammonia content in effluent, after a series of violations. MBBR technology has proven to work well in cold temperatures. In 2022, new clarifiers are expected to come online, increasing the WWTF’s capacity.

● The Village Safe Water program (VSW) is an initiative of AK DEC, in collaboration with the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, to improve water and sewer systems in rural communities across the state. The VSW carries on work previously funded by USDA-RD Rural Alaska Village Grants. Many Native Alaskan villages are “unserved” or only partly served by sanitary water and sewer systems. Innovative systems for onsite wastewater treatment and reuse for single homes or clusters of homes are being developed and installed, along with traditional systems of pipes and treatment facilities. https://dec.alaska.gov/water/village-safe-water/