State Data

Confidence in data for this state:

LOW

2018 data unless noted.

Definitions

Terms used on this website and in data sets are defined & discussed here.

Biosolids land application. Photo courtesy of NEBRA.

State Statistics Dashboard

State Summary

● Mississippi is the poorest state in the Union, and its wastewater infrastructure is underfunded and in need of upgrading. Data on the use and disposal of MS wastewater solids are incomplete.

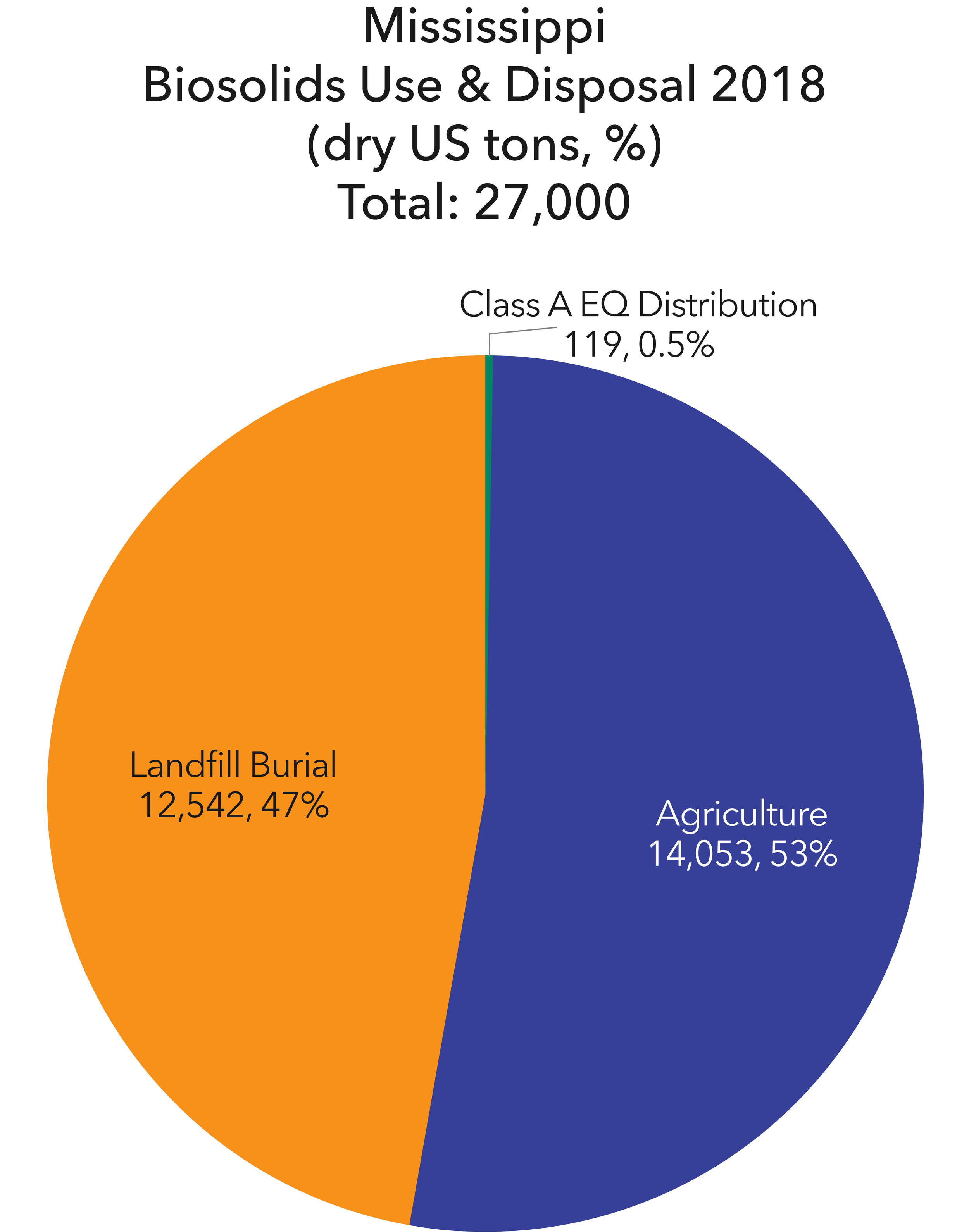

● NBDP estimates that about half – perhaps ~11,000 dmt – of Mississippi’s wastewater solids are disposed of in landfills, and, in 2018, that included the solids from many small WRRFs (including the MS Band of the Choctaw WRRF) and likely some lagoon systems that were dredged that year. A considerable amount of MS wastewater is treated in Memphis, TN, which disposes of its solids at a monofill. (Those solids are counted in the TN data, not here.)

● There is no incineration of MS wastewater solids.

● Land application of Class B biosolids on agricultural lands accounts for almost all of the beneficial use of biosolids in Mississippi. Jackson, the largest city (population ~164,000) land applied 4,093 dry metric tons of Class B biosolids in 2018 (and landfilled 283 dmt). The county utility authorities of Harrison (which includes Gulfport and Biloxi, the 2nd and 4th largest cities, respectively), Hancock, Pearl River, and Jackson County all land applied Class B biosolids. Jackson County (which is not near Jackson but is in southeast MS) operates four WRRFs and a land application facility at its West Jackson County WRRF, where the biosolids help grow Bermuda grass for hay sold for livestock feed.

● Many Mississippi WRRFs – especially smaller ones – rely on lagoons for wastewater and solids treatment because they are simpler and less expensive than mechanical treatment plants. Solids are dredged from lagoons every 5 – 30 years. Hattiesburg is an example of a larger city (the state’s 5th largest, at ~46,000 people) that relies on lagoons; it has two: North and South. The South Lagoon was dredged in 2013, at a projected cost of $6 million, producing 11,000 dry U.S. tons of solids that were likely mostly land applied. Most recently, as of 2022, Hattiesburg and three other large MS cities (Jackson, Meridian, and Greenville), whose infrastructure have decayed because of lack of funding, are under U.S. EPA consent decrees for WRRF improvements.

● The Waste Division of the MS DEQ oversees biosolids use and disposal. The state’s biosolids coordinator identified pressures on biosolids management in the NBDP state survey:

COST – rising costs generally

REGULATIONS ON BENEFICIAL USE – lack of regulatory support for beneficial use

MANAGEMENT ISSUES – the hassle of biosolids recycling/land application

PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT – concerns of neighbors, environmental groups, and others

NUISANCE ISSUES – odors, truck traffic, dust, etc.